Are you buying good spices… or bad?

Spices are at the heart of global trade and movement. They add sparks of flavour to our cooking and are key to many cuisines, yet we don’t often think about how they are produced. Anna Sulan Masing investigates the spice route and asks what choices we should make to ensure the ones we use have a positive impact on the environment and the people who grow them…

Where do spices come from?

When you reach into your spice cupboard, do you give its contents’ origins the same attention you give when selecting fresh produce? Writer and chef of Empress Market, Numra Siddiqui, explains that she is very specific when choosing spices, “I spend a lot of time reading labels and fine print. I look for plump green cardamon pods, tightly wound cinnamon sticks, bright orange turmeric.” Noting where spices are from is important, and she likes to buy from Pakistan when she can, where she is currently developing a spice project with Pakistani farmers. Spices travel so far, it can be easy to forget that they are agricultural products. Due to an exploitative colonial history there are opaque and complex sourcing structures of endless middlemen that involve brokers, buyers, warehouse storage, exporters, importer, sellers… which ultimately mean the farmers can see very little reward.

Broadly speaking spices are seeds, roots, berries and bark grown in warm regions. Spices have a long history and have been associated with medicines, foods, perfumes and rituals, and still hold fascination and intrigue. Because spices could be dried, ground and their oils preserved while still retaining so much taste and aroma, they were excellent ingredients to be traded.

Ancient Rome adored black pepper – which is how we have the (still) popular dish of cacio e pepe. Although originally from South Asia, turmeric was spotted in China by Marco Polo. Cumin, native to the Middle East, is a key ingredient in Mexican mole; and the Sri Lankan spice, cinnamon, is a favourite in Nordic baking. Spices travelled and became part of new culinary cultures wherever they went.

"Spices are ingredients, but they are also about culture and trade."

Who grows spices?

Spices are now grown outside of their place of origin and there are many different farming techniques. For example, Malaysian black pepper is mostly grown by indigenous communities on small family-run farms deep in the Borneo jungle. The vines are tended to daily, once ripe the berries are hand picked and dried under the sun until black, before traversing up river to a co-op to be processed and exported.

Turmeric, part of the ginger and galangal family, is grown across the equator from Vietnam to Nicaragua. US-based spice company Burlap & Barrel co founder, Ethan Frisch, describes the small turmeric farm in Southern India they work with, run by a former Ayurvedic pharmacologist, “he relies on rain water, rather than irrigation, traditional fertilisers based on jaggery and Gir cow urine and dung; he approaches farming as much as a spiritual activity as a commercial one.”

"Spices are often grown by small family farms, vulnerable to inequitable global trading structures."

The history of spice is complex, why is that important?

The world we live in has been shaped by the desire for spices so it is impossible to separate these ingredients from economics. Throughout the Middle East there was an ancient thriving spice trade, and dating back to at least the third century AD, there were dynamic networks across the Indian Ocean that brought pepper from India and produce from the Borneo jungle to China; and nutmeg, mace and cloves from the Indonesia archipelago went to Mecca and eventually to Venice and Europe. The Mongolian Empire stabilised regions making cross-country trading travel safer and the ‘Silk Road’ took shape.

It was the quest to find the ‘Spice islands’, now known as the Banda islands in Indonesia, to reap financial gains that set Christopher Columbus en route west in 1492. Instead he stumbled upon the Caribbean and kicked started a brutal colonial regime in the Americas. But, these voyages also brought chillies to Asia and allspice to the Levant. Where people go, food travels. The first British East India Company fleet brought back ships laden with Indian black pepper in 1603, which laid the foundations for Britain’s exploitative colonial project in Asia. Spice plantations were developed in colonial spaces, which used enslaved people, indentured labour and exploited native workers, for the financial gain of European countries.

Why is sourcing important?

Companies who have a close working relationship with farmers are able to have shorter supply chains, meaning they can offer farmers a higher price for the crops. Higher incomes mean farmers are able to invest back into their communities and environment. Angus Aarvold, founder of Hill & Vale spice company in Bristol, describes their relationship with pepper farmers in Kerala, “we’ve been able to work with farmers to grow different varieties of black pepper to help support a more biodiverse sector.” Farmers have naturally gravitated to higher yield varietals, putting heritage or native varieties at risk.

“From a food security perspective this also poses a risk should disease or crop failure occur,” Aarvold explains. But direct sourcing isn’t easy, as it involves travel, trust and relationships: Hill & Vale currently work with an importer for their cumin who works with a variety of organic producers in Pakistan, as they continue to develop trade links.

Aarvold says that traceability is also a matter of quality, “product adulteration is still a big problem in the herb and spice world, so working directly with farmers means we can avoid some of these potential pitfalls.”

A more sustainable future for spice farming?

Spice growing countries are at the front line of climate change, with the issue of dramatic weather changes, such as floods and high temperature affecting fruit development, soil erosion and seed maturity. Being innovative and re thinking systems is crucial in continuing spice farming.

This is often about slowing down and re-integrating traditional techniques, such as shifting cultivation to give soil a rest, and ensuring a polyculture practice is happening. In Indonesia, small holder cinnamon farmers are being encouraged to grow patchouli and coffee alongside cinnamon. Patchouli can be harvested quickly, which allows farming communities to be financially stable, and coffee enjoys the shade of the cinnamon trees.

In parts of Afghanistan cumin is still foraged from the wild; by carrying the dried cumin plants through the mountain villagers distribute seeds along the way, ensuring new crops each year. Burlap & Barrel are paying for wild cumin via a traditional money-transfer network called hawala, as modern banking systems don’t serve Afghanistan.

"Trusting in traditional spice-growing methods is innovative and better for the environment."

Where and how to buy more sustainable spices

When it comes thinking about sustainability and spices, sourcing is the key. Ask these questions when looking at the pack and choosing spices:

- Can you see the place of origin?

- Is there a way to find more information on supply chain?

- Does the ingredient list ONLY list the spice?

- Are there farm names and harvest dates?

Here are some UK companies that are doing great work:

Feeling inspired? Try these simple new recipes that showcase the brilliance of sustainable spices…

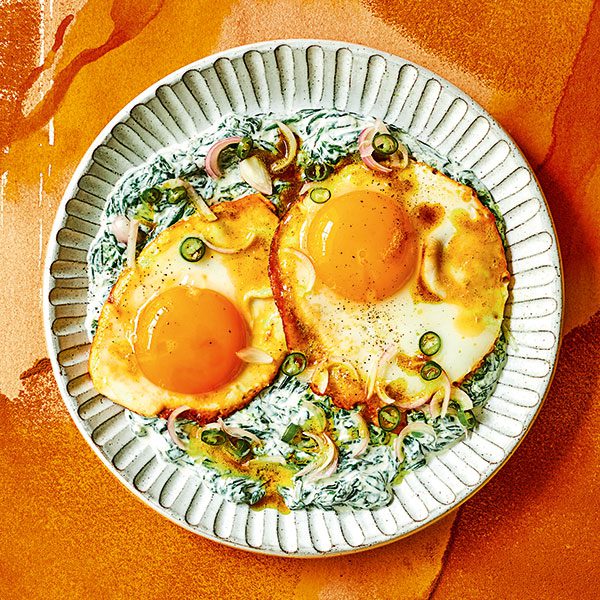

Turmeric eggs with spinach and pickled shallots

In this healthy recipe, eggs are fried in earthy turmeric butter and scattered with quick pickled shallots and chilli.

Easy flatbreads with cumin seed butter

A pile of warm, pillowy flatbreads are always a hit, and infusing nutty butter with cumin seeds to brush over them while hot makes these even more appealing.

How to enhance a brunch favourite? Make a quick flavoured butter packed with cinnamon’s gentle warmth. It really takes this French toast up a notch.

There is a citrussy zing to these buttery biscuits which is then swiftly followed by a prickly heat of black pepper with every bite. It brings out the sweetness perfectly.

Subscribe to our magazine

Food stories, skills and tested recipes, straight to your door... Enjoy 5 issues for just £5 with our special introductory offer.

Subscribe

Unleash your inner chef

Looking for inspiration? Receive the latest recipes with our newsletter