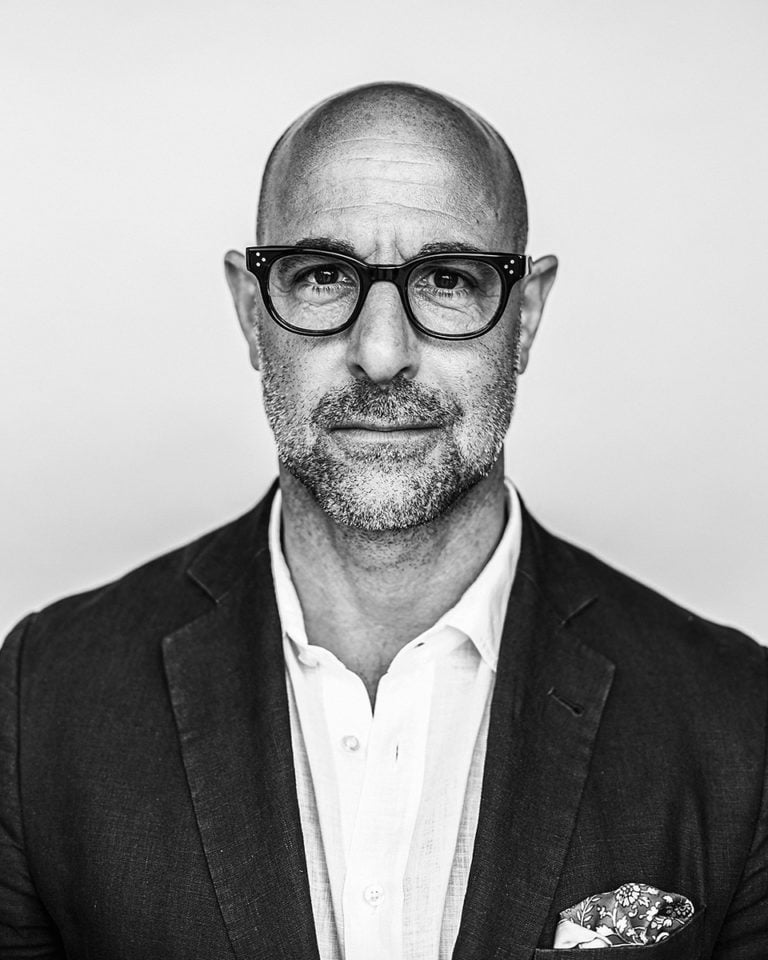

Diana Henry meets…Nigel Slater

What happens when two of the UK’s best-loved food writers get together for a chat over a cup of tea? How refreshing to find that Diana Henry and Nigel Slater have the usual anxieties, from rapid house-tidying to making a cake and worrying whether the other will like it…

Conversation and coffee cake

Nigel has had a terrible morning. “Me too,” I say, explaining that electricians arrived at 7am. “But I had flashing lights and the emergency services!” he exclaims. He’d burnt his toast, setting off the alarm in his kitchen. This is strangely comforting: Nigel Slater burns toast, and he’s not hiding it.

Because he has such a gentle manner and is wearing the softest grey hoodie (I’m guessing cashmere), you want to hug him, to make the burnt toast disappear. So I’m glad I’ve made a coffee and walnut cake, his favourite, though the baking of it was stressful. I was so nervous that the first bowlful of batter ended up on the floor. Coffee cake two – I’ve made it as my mum used to and it looks worthy of a WI sale – is sitting before us. I also spent days sorting out my books and paperwork (they usually cover a third of the kitchen table) and tidied the sea of bottles beside the cooker for Nigel’s visit. My children are familiar with the interior of Nigel’s home as, every so often – in a magazine or in one of his books – you get glimpses. It’s uncluttered, almost monastic, filled with carefully chosen colours and objects. They tell me that Nigel would find my house so untidy it would be traumatic for him. (They’re only half joking.)

“I was so nervous making a cake for Nigel that the first bowlful of batter ended up on the floor.” - Diana

Simple, delicious food

Why all this effort? Because though food writers can become important in your life – their recipes form part of your home’s rhythm – few actually change the way you look at food. For me, Nigel Slater did. I remember the first time I saw his work in Marie Claire magazine (the piece is still somewhere in my two enormous boxes of Nigel cuttings). At the time – the mid 1980s – food was either shot in a graphic way (dots of purée on huge white plates) in ‘foodie’ magazines such as A La Carte, or in a dull, over-propped fashion for women’s magazines. The piece I tore out from Marie Claire was about picnics and, instead of the usual sandwiches, it featured radishes with creamy-white French butter and baguette and berries with ricotta. You could see the beaut in every element: the crimson of the radishes against the pale butter, the workaday loveliness of Duralex glasses, the well-worn cutlery. Nigel showed you the beauty in the domestic and the seemingly ordinary. If you looked at the world through his eyes, it was a better place. His food was simple too. Back in the 1980s, ‘simple’ food was someone telling you how to turn a can of condensed soup and some chicken breasts into a gratin. Nigel could take a few good ingredients and do something truly smart and delicious with them.

“For me, food is associated with other worlds. I was brought up in a twitching-curtains kind of place and I longed to go somewhere else.” - Nigel

As documented in his memoir, Toast, he had a difficult childhood and a lonely adolescence. His mum, a hopeless cook who nevertheless made him toast (which he loves), died when he was just nine years old; his father was cold and disappointed in him, and his stepmother was just plain mean. I theorise that those who’ve had tough childhoods turn to food because it’s associated with care. “No, it’s associated with other worlds,” he says. “I was brought up in a twitching-curtains kind of place, and I longed to go somewhere else. I would think to myself, ‘Surely it’s not like this in London?’”

Career beginnings

Overcoming anxiety – he jokes that he’s “scared of his own shadow” – he was bold enough to ask for a job at Justin de Blank’s, a high-class traiteur in Belgravia. He also wrote to Elizabeth David to see if she wanted help with her books. She wrote back saying, no, she didn’t get help from anyone. “Then she went into rant mode about writers who didn’t do their own stuff,” he laughs. While at Justin de Blank’s, he was offered work at A La Carte, then landed his breakthrough job at the newly launched Marie Claire and, finally, moved to The Observer, where he has been for nearly 30 years.

I’ve always found it hard to choose my favourite of I’ve always found it hard to choose my favourite of his books. Appetite, with its subtitle, ‘What do you want to eat today?’ gave me the answer to the question we all whisper to ourselves on the way home to make supper. Then there’s his fruit book, a tome that lives on the floor beside my bed. The photographs are so rich that leafing through it is like visiting an art gallery before you go to sleep. Jonathan Lovekin photographed these, but it’s Nigel who composed the pictures, offering – in one memorable instance – poached peaches in a Japanese bowl.

The essence of Nigel’s cooking

So I was surprised when his latest volume, A Cook’s Book (Fourth Estate £30), went straight to the top of my list. First, it’s a book you could use for the rest of your life; 500 pages of pies and stews and cakes you want to make immediately. Second, it covers everything you might have pondered in your own kitchen as you were making soup (How can I make it better?) or looking at a dead sourdough starter (What went wrong?). It’s also a manifesto, a re-stating of what is at the core of Nigel’s cooking – the need to make something simple, just, as he puts it himself, “something to eat, really”. Onions with miso and sake, potato gratin with dill and camembert, marmalade treacle tart.

The book is also about Nigel. Apart from autobiographical stories on foods remembered and loved (the first baguette, eaten in Paris), there are more photographs of the cook and his home than usual. Finally, it’s a book about love. Every one of Nigel’s books has the love of food as an accepted subtext, but here it’s intense, present in every meandering thought. The book is like a long conversation with the reader, punctuated by recipes. He tells us he always cooks too much rice and that he’s wondered whether he’d like to die in a deserted Japanese forest or while eating chips with béarnaise.

He has always had a direct voice, but there is a new intimacy in this book. “It might be because I wrote it during lockdown,” he says. He is shy in person, but not on the page, and I’m not surprised that this level of communication, at a time when he wasn’t seeing anyone, was draining. By the end, he says, he was exhausted.

“People stop me and say ‘I made your dish…’ and I immediately worry it might not have worked.” - Nigel

Being shy and also famous is difficult. He loves his own company and often travels by himself (especially to Japan, where he would like to live). He hates dinner parties and awards ceremonies (arriving at one awards ceremony he surveyed the room, had an anxiety attack and got back in his cab). He doesn’t do tours like other food writers, except for an event in Germany. “I thought I was kind of hidden there, so if it all went wrong it wouldn’t matter.” Doesn’t he mind being spotted by readers when he’s out shopping? “No, they’re so kind, so warm. They read my columns, they buy my books, I’m happy to give them my time. Although they often start off with ‘I made your dish…’ and I immediately worry it might not have worked.”

Nigel has ended up in the ‘other worlds’ he longed for as a child. Given his exceptional eye, his ‘cook-me-now’ recipes and glorious writing – so sensual you wonder if he spends his time like a still-life artist, looking hard at tomatoes or raspberries until he can describe their very essence – I’m surprised that he’s anxious, particularly about the thought of one day losing his column at The Observer. “I’ll keep writing until they don’t want me. Then I’ll just write the books.” I protest that this would never happen, that there would be an outcry. “You know what it’s like, though,” he counters. “It just takes a new editor who wants to make their mark and that’s it.” I’m not sure he knows how much he’s loved. Perhaps a harsh childhood means you can’t feel it even when there’s a tsunami of it coming towards you.

He’s had two slices of coffee cake and we’ve talked for ages. I wish he’d stay. I want to show him the cookbooks I’ve recently bought… But I know he’ll want to spend time on his own now. I wrap up another big chunk of the cake, say goodbye and triumphantly yell at my children – who are upstairs – “Hey guys, Nigel Slater loved my coffee cake!”

A Cook’s Book by Nigel Slater (Fourth Estate £30) is out now

Subscribe to our magazine

Food stories, skills and tested recipes, straight to your door... Enjoy 5 issues for just £5 with our special introductory offer.

Subscribe

Unleash your inner chef

Looking for inspiration? Receive the latest recipes with our newsletter